Exercise and the gut microbiome

The gut microbiome is an incredible thing: around 37 trillion microbes living largely in our lower intestines and weighing in at approximately 2 kilograms. Given we have only 30 trillion human cells in our bodies, one would expect the microbiome to have some big biological effects. And that’s what we see. This ecosystem of bacteria, viruses, fungi, archaea and eukaryotes affects many aspects of our health from our immune systems, energy use, mood, oxidative stress, ageing and of course our gut health.

It is unsurprising that our diet affects our microbiome. After all what we eat becomes the environment the microbes live in and a source of their nutrients too. But what about that other staple of a healthy lifestyle - exercise? Does that affect our microbiome?

We’ve looked at the scientific literature that addresses this specific question. The answer may surprise you.

Regular moderate exercise boosts butyrate producers

Studies in mice and rats were the first to indicate that moderate or voluntary exercise can change the microbiome in ways that are generally viewed as positive.

In particular, exercise training increases the relative abundance of butyrate-producing bacteria. Butyrate is a short chain fatty acid (SCFA) produced when certain bacteria ferment dietary fibre.

Butryrate is the main fuel for colon cells and has been shown to promote cell proliferation and cell turnover in healthy colon cells, effectively strengthening the gut barrier.

In contrast, a build up of butyrate in colon cancer cells suppresses proliferation and promotes cell death and tumour shrinkage.

Butryrate also helps to regulate the host immune system and gene expression.

Of Mice and Men?

Animal studies are a great starting point, but at the risk of stating the obvious, we are humans, not mice!

So are what do we see in human studies? There have been many studies comparing two groups: sedentary people and those that do regular exercise. The researchers again saw differences in the gut microbiomes in these different groups.

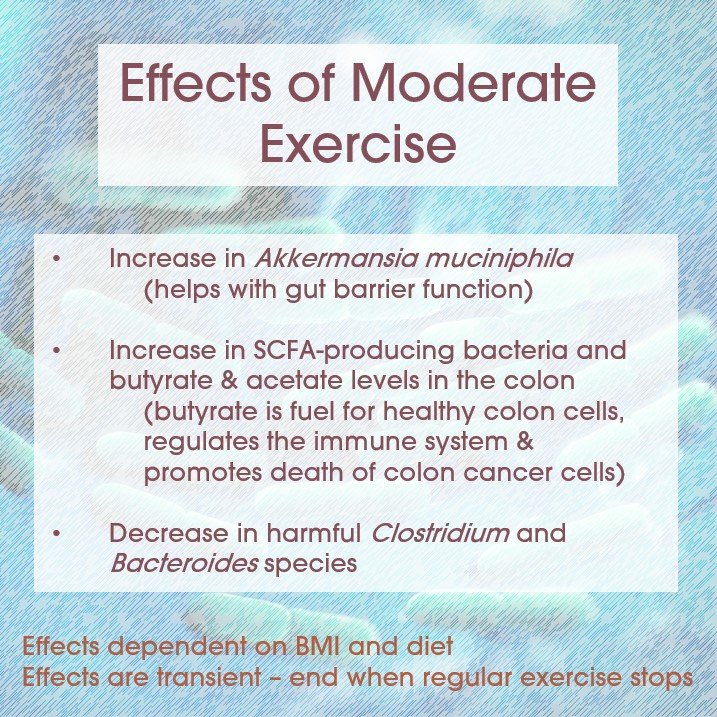

For example, a study comparing women who performed at least 3 hours of exercise per week with sedentary women found that the active women had increased levels of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia hominis, which are known butyrate producers. They also had increased Akkermansia muciniphila, which increases mucus thickness and gut barrier function.

However, active people tend also to have different diets from their sedentary counterparts, for example the exercising women ate more fuit and vegetables, making it unclear what is actually causing the changes in the gut microbiome.

Longitudinal studies

More recent studies followed the same individials over time as they start and/or stop exercise and keep diet constant. These are the most useful.

One of the best examples is from Jeffery Wood’s research Group at the University of Illinois. They followed participates as they undertook a 6-wk supervised endurance exercise program (30- to 60-min duration, 3 times per week).

The lean participants saw an increase in Faecalibacterium species and a decrease in Bacteroides species with exercise. The six weeks of exercise also increased the abundance of butyrate producing bacteria and concentrations of two SCFAs: acetate and butyrate in poo samples.

A different research group looking at the effects of light to moderate exercise (cycling) in women found many responded with increases in Akkermansia muciniphila.

Exercise can also decrease the abundance of harmful bacteria such as Clostridium difficile and Bacteroides fragilis.

The results then are much like the studies above, but Wood’s group and others have found that the positive effects are dependent on BMI (with quite different effects in obese participants), diet (whey protein helps) and that they are transient - i.e., they disappear after a few weeks once exercise stops.

How might exercise have these effects?

More research is need to clarify the mechanisms that underpin the changes seen in the microbiome with regular exerise. But some possibile candiates are:

Exercise increases the motility of the gut - making the contents move through faster and perhaps be mixed more thoroughly.

Exercise affects the amount of bile acid released changing the chemistry of the gut’s contents.

Exercise affects the immune cells found in the intestine and the ant-inflammatory chemicals they produce.

Blood flow away from the gut during exercise and the rise in body temperature indirectly affect the gut the microbiome through changes in the intestinal cells and the integrity of the gut barrier.

Metabolites such as lactic acid may be absorbed into the gut and affect the microbes.

Exercise may ‘train’ the gut cells to form a more resilient gut barrier in the longer term.

How might the microbiome changes impact health?

Researchers have speculated that the microbiome changes caused by exercise have far reaching effects on gut and general health.

Akkermansia muciniphila has been associated with a lean body mass index (BMI) and improved metabolic health.

We mentioned how SCFAs, especially butyrate, strengthen the gut barrier. Mouse studies have shown that it can also promote the death of colon cancer cells. This may be the mechanism by which exercise reduces colon cancer risk.

Butyrate also reduces pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress in the gut. Researchers have speculated that it may have beneficial effects on Crohn’s disease as well as insulin resistance and immune health, but more research is needed.

The more exercise the better, right?

You’d think so, but no. When researchers look at the microbiome of elite athletes a different pattern emerges.

For example, researchers comparing elite rugby players to lean, but non-active controls found a greater diversity of bacteria in the gut microbiome in the rugby players, but they had reduced Bacteroides, Lactobacillaceae and Lactobacillus species compared with lean controls. The latter at least are generally seen as beneficial.

Similarly, a 2022 review looking across many studies found that athletes harbor a more diverse type of intestinal microflora than non-athletes, but with a relatively reduced abundance of SCFA- and lactic acid-producing bacteria, thereby suggesting an adverse effect of intense exercise on the population of gut microbiota.

The authors concluded that increasing the intensity and volume of exercise over a long period may lead to gut dysbiosis.

It appears that exercise can alter the pH and oxygen levels in the gut, which may affect the growth and survival of some bacteria. Intense or prolonged exercise can also induce stress hormones, such as cortisol, which may suppress the growth of beneficial bacteria and promote the growth of pathogenic bacteria. It can also increase intestinal permeability, which allows bacteria and their metabolites to leak into the bloodstream and cause systemic inflammation.

This may explain why many elite athletes experience what is called “exercise-induced gastrointestinal syndrome”. This is 1.5 - 3 times more common among qualified athletes than among amateurs. It causes symptoms of abdominal pain, colic, flatulence, nausea, vomiting or diarrhea.

If we go back to the mouse studies, we see a similar pattern. Voluntary exercise in the mice leads to beneficial changes in the microbiome, whilst forced exercise causes harm.

Key takeaways

Moderate exercise is certainly beneficial for your gut health.

If you aren’t currently undertaking regular exercise, this is another good reason to start. That can be hard if you’ve never enjoyed sport. Simple ways to gently get moving are to add in walks to the shops or walks with friends on the weekend.

Once you’ve developed some stamina and you want to really get your heart going without stressing your joints, incline walking is a great way to go. Head for the treadmill at the gym, set the incline to 6, speed to 3 and walk for 20 to 30 minutes. And here’s the trick if exercise hasn’t previously been your thing - you can watch your favourite tv show or listen to a podcast at the same time. Yay! Build up to an incline of 12 as your fitness increases.

2. High training levels can be harmful to your gut microbiome.

Researchers are still working out what probiotics or dietary change might help ameliorate the negative effects of high levels of exercise. But a good place to start is likely to be adding more fibre (try our Superflora range of shakes and boosts for great tasting fibre packed options), plant-based foods and fermented dairy or probiotics to your diet.

Adding quiet mindfulness, breath work or yoga that help to switch on your parasympathetic nervous system (= your everything is ok, rest and digest system) may also help balance out the effects of intense or prolonged exercise.

Written by: Dr Mary Webberley, Chief Scientific Officer at Noisy Guts. Mary has a background in biology, with two degrees from the University of Cambridge and post-doctoral research experience. She spent several years undertaking research into the diagnosis of IBS and IBD. She was the winner of the 2018 CSIRO Breakout Female Scientist Award.

Key papers:

Dziewiecka, H., Buttar, H.S., Kasperska, A. et al. Physical activity induced alterations of gut microbiota in humans: a systematic review. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 14, 122 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-022-00513-2

Mailing LJ, Allen JM, Buford TW, Fields CJ, Woods JA. Exercise and the Gut Microbiome: A Review of the Evidence, Potential Mechanisms, and Implications for Human Health. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2019 Apr;47(2):75-85. doi: 10.1249/JES.0000000000000183. PMID: 30883471.